The Supreme Court Today (April 16) strongly criticized the Telangana government for cutting trees in Kancha Gachibowli near Hyderabad University, calling it an environmental crisis. It ordered a complete stop to tree felling and promised to go “out of the way” to protect nature.

Earlier, on April 3, the Supreme Court had taken suo motu cognisance (meaning the Court itself started the case without anyone filing a petition) of the Telangana government’s tree-cutting drive in the Kancha Gachibowli forest area. The Court had called it a “very serious” issue.

It asked the Telangana government to give reasons for such a “compelling urgency” behind cutting down so many trees. The Court also ordered a complete stop to all tree-cutting and development activities on that land until further notice.

This entire controversy started when students from the University of Hyderabad began protesting the state government’s plan to develop a 400-acre land that is right next to their campus. The students were worried that the plan would destroy a valuable green area, home to many trees and animals.

The next hearing of the case will be held on May 15, and until then, the Supreme Court has made it clear that nature must not be disturbed anymore.

On April 3, the apex court took suo motu cognizance of the deforestation activities occurring in the Kancha Gachibowli forest, directing that no activities, except for the protection of existing trees, should be undertaken by the state or any authority until further orders.

The case arose after news came out that trees were being cut down to make way for land development. People living nearby and students from the University of Hyderabad say that the forest is home to many plants, animals, and birds. Cutting down the trees not only destroys nature but also affects the local climate and water levels.

The report further noted the presence of peacocks, deer, and various birds in the area, suggesting that a forest habitat existed for these wildlife species.

The bench instructed the chief secretary of Telangana to address several inquiries, including whether the state had obtained an Environmental Impact Assessment certificate for the proposed developmental activities and if the necessary permissions from forest authorities or local statutes were secured for tree felling.

Additionally, the Supreme Court requested that the central empowered committee visit the site in question and submit its findings before April 16.

Students from the University of Hyderabad have been protesting against the state government’s plans to develop the 400-acre land parcel next to the university.

Student groups and environmental activists have raised their voices against the development plan, saying it will harm the environment and nature.

This case is not only about one forest, but also about how India manages development while taking care of nature. People are hoping the court will give a fair decision that protects both people’s rights and the environment.

The Supreme Court’s action in Kancha Gachibowli Forest is a pivotal moment for environmental governance in India.

![cover]()

How many species do we share our planet with? It's such a basic and fundamental question to understanding the world around us.

It's almost unthinkable that we would not know this number or at least have a good estimate. But the truth is that it's a question that continues to escape the world's taxonomists.

An important distinction is how many species we have identified and described and how many species there actually are. We've only identified a small fraction of the world's species, so these numbers are very different.

How many species have we described?

Before we look at estimates of how many species there are in total, we should first ask the question of how many species we know that we know. Species that we have identified and named.

The IUCN Red List tracks the number of described species and updates this figure annually based on the latest work of taxonomists. In 2022, it listed 2.16 million species on the planet. In the chart, we see the breakdown across a range of taxonomic groups — 1.05 million insects, over 11,000 birds, over 11,000 reptiles, and over 6,000 mammals.

species, in biology, classification comprising related organisms that share common characteristics and are capable of interbreeding. This biological species concept is widely used in biology and related fields of study. There are more than 20 other different species concepts, however. Some examples include the ecological species concept, which describes a species as a group of organisms framed by the resources they depend on (in other words, their ecological niche), and the genetic species concept, which considers all organisms capable of inheriting traits from one another within a common gene pool and the amount of genetic difference between populations of that species. Like the biological species concept, the genetic species concept considers which individuals are capable of interbreeding, as well as the amount of genetic difference between populations of that species, but it may also be used to estimate when the species originated.

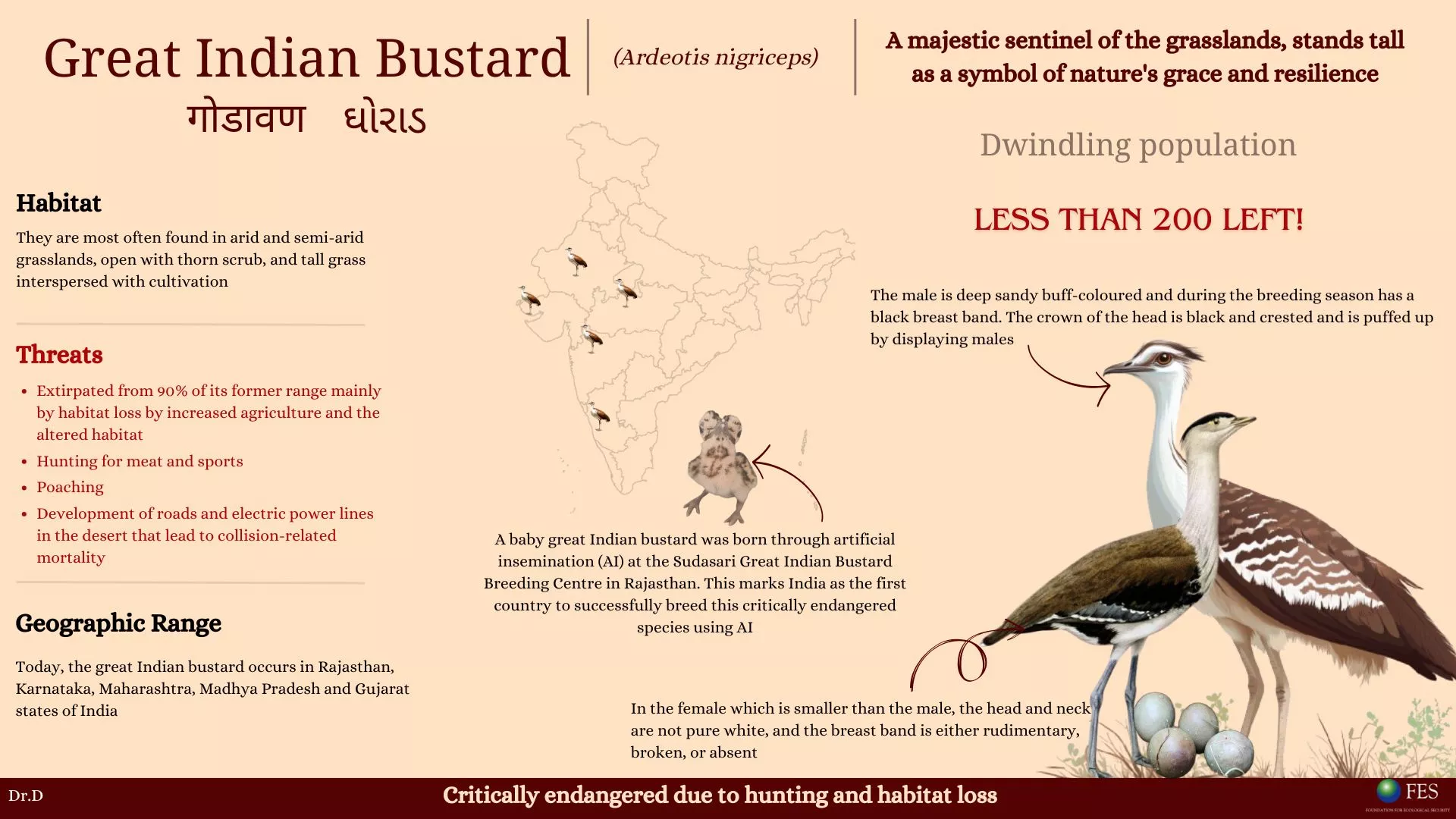

In the vast, arid landscapes of Rajasthan, a majestic bird once soared freely across the skies—the Great Indian Bustard. Known for its striking appearance and graceful flight, this bird symbolised the region's rich biodiversity. However, as time passed, the great Indian bustard's numbers began to dwindle, and today, less than 200 of these magnificent creatures remain in India.

I witness the struggles of the great Indian bustard as it fights for survival against overwhelming odds. The threats it faces, such as habitat loss, poaching, and collisions with power lines, are deeply unsettling. This situation presents a dilemma of “Green” versus “Going Green.” As our human settlements expand and agricultural practices become more intense, the beautiful grasslands that the bustards once called home have been transformed into farmlands and urban areas. This drastic loss of habitat has left these magnificent birds with fewer safe spaces to forage and breed, and it’s a tragic reminder of the impact our choices have on the natural world.

Poaching has taken a heavy toll on the bustard population. Despite being protected by law, these birds are hunted for their meat and feathers. The installation of power lines across their habitats has further exacerbated the situation. The bustards, with their poor frontal vision, often failed to see the wires and collided with them, leading to fatal injuries.

Recognizing the urgent need to save this species from the brink of extinction, conservationists and local communities joined forces. They launched initiatives to restore and protect the bustard's habitat, creating safe zones where the birds could thrive. Efforts were made to bury power lines underground or mark them with bird diverters to prevent collisions.

One notable example of community efforts in conserving the Great Indian Bustard (GIB) is the "Godawan Community Conservation Project" in Rajasthan. This project, initiated by wildlife biologists Sumit Dookia and Mamta Rawat, involves local youth from villages around the Desert National Park (DNP) in Jaisalmer.

Local youth are trained to become nature guides, providing them with employment and instilling a sense of pride and ownership towards the GIB. The guide helps conservationists track the GIB's location and report any poaching attempts to the forest department.

This collaborative approach has helped build a supportive community network that actively participates in protecting the critically endangered GIB. Education and awareness campaigns were also crucial in changing local attitudes towards the bustards. Communities were encouraged to take pride in their natural heritage and participate in conservation activities. Poaching laws were strictly enforced, and alternative livelihoods were provided to those who depended on hunting.

One of the most significant breakthroughs came with the advent of artificial insemination techniques. In a historic milestone, a Great Indian Bustard chick has been successfully born through artificial insemination in Rajasthan. Ashish Vyas, a local Divisional Forest Officer, expressed his excitement, stating, "This is the first instance of a great Indian bustard being bred through artificial insemination. This breakthrough will enable us to save the sperm of these rare birds, create a sperm bank, and eventually increase their population."

Scientists at the Sudasari Great Indian Bustard Breeding Centre in Jaisalmer successfully bred a chick through this method, offering a glimmer of hope for the species' future. The process involved collecting sperm from a three-year-old male bustard named Sudha and inseminating a five-year-old female named Toni. Toni laid an egg on September 24, which was carefully monitored by scientists. The egg hatched on October 16, resulting in a healthy chick. After a week of observation and medical tests, the chick has been confirmed to be healthy.

This achievement demonstrated that it is possible to increase the bustard population and secure their survival with the right technology and dedication.

The story of the great Indian bustard is a demonstration of nature's resilience and the power of collective action. It reminds us that even in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges, there is always hope. By continuing to mitigate the threats to their survival and fostering a culture of conservation, we can ensure that these magnificent birds continue to grace the skies of India for generations to come.

🌻

Dr.D